The reason I started writing this blog, is to document my work on getting an Arduino board talking to an Acorn Econet network. The Arduino has MicroSD storage, and an Ethernet port (via a commonly available shield) , both of which I hope to make resources available on the Econet network. This should be better way of providing file and gateway resources onto an Econet network, than the solutions I spoke about in the previous blog post.

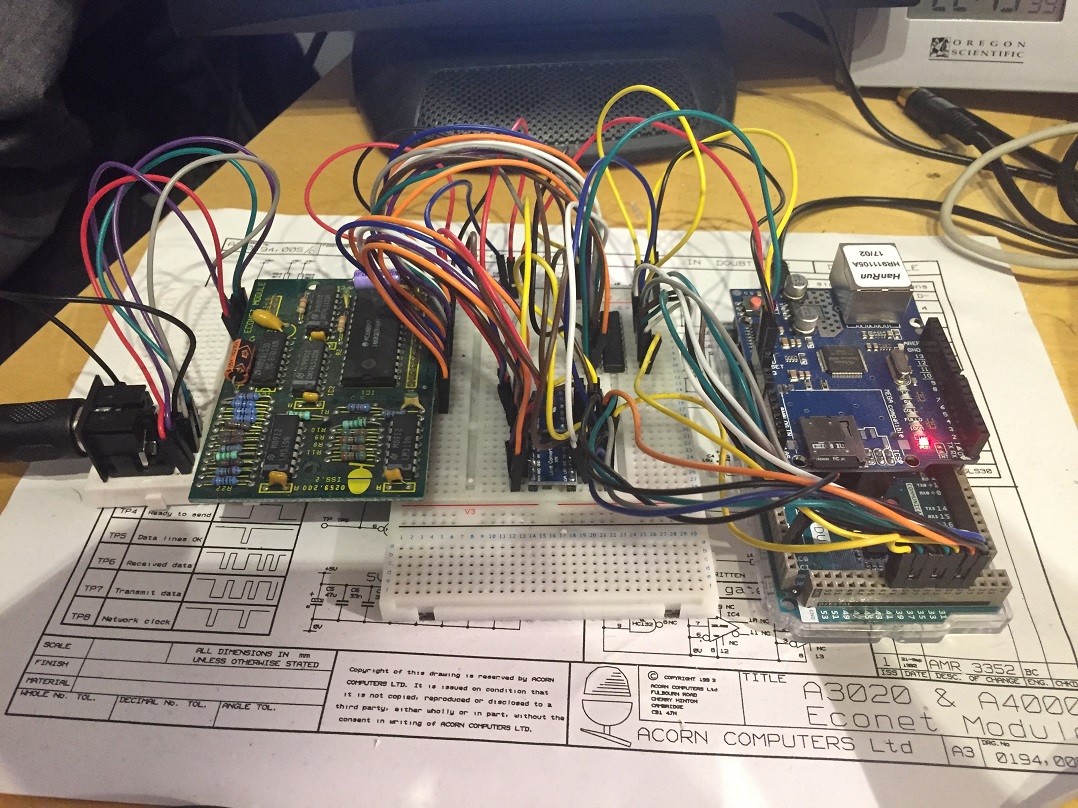

It turns out that with an Arduino Due and a couple of level shifters you can just about communicate with an Econet card, and successfully load and send frames to an Econet network:

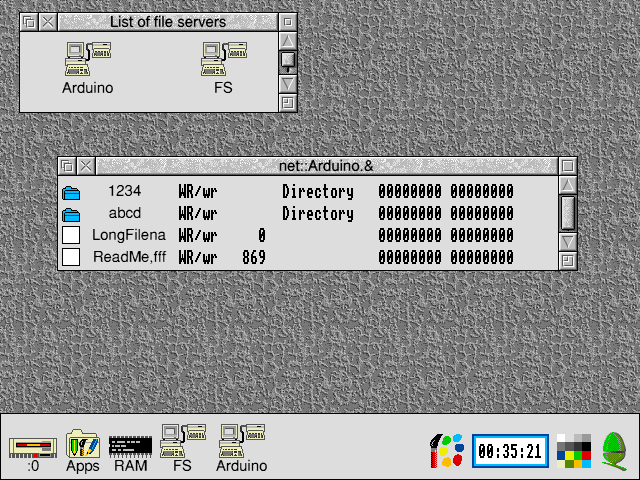

And after several evenings of programming I’ve finally got to the stage where I can log on to the Arduino, and display the user directory on the SD card:

Right now there isn’t anything else you can do, other than logoff. But it’s a good start to work from.